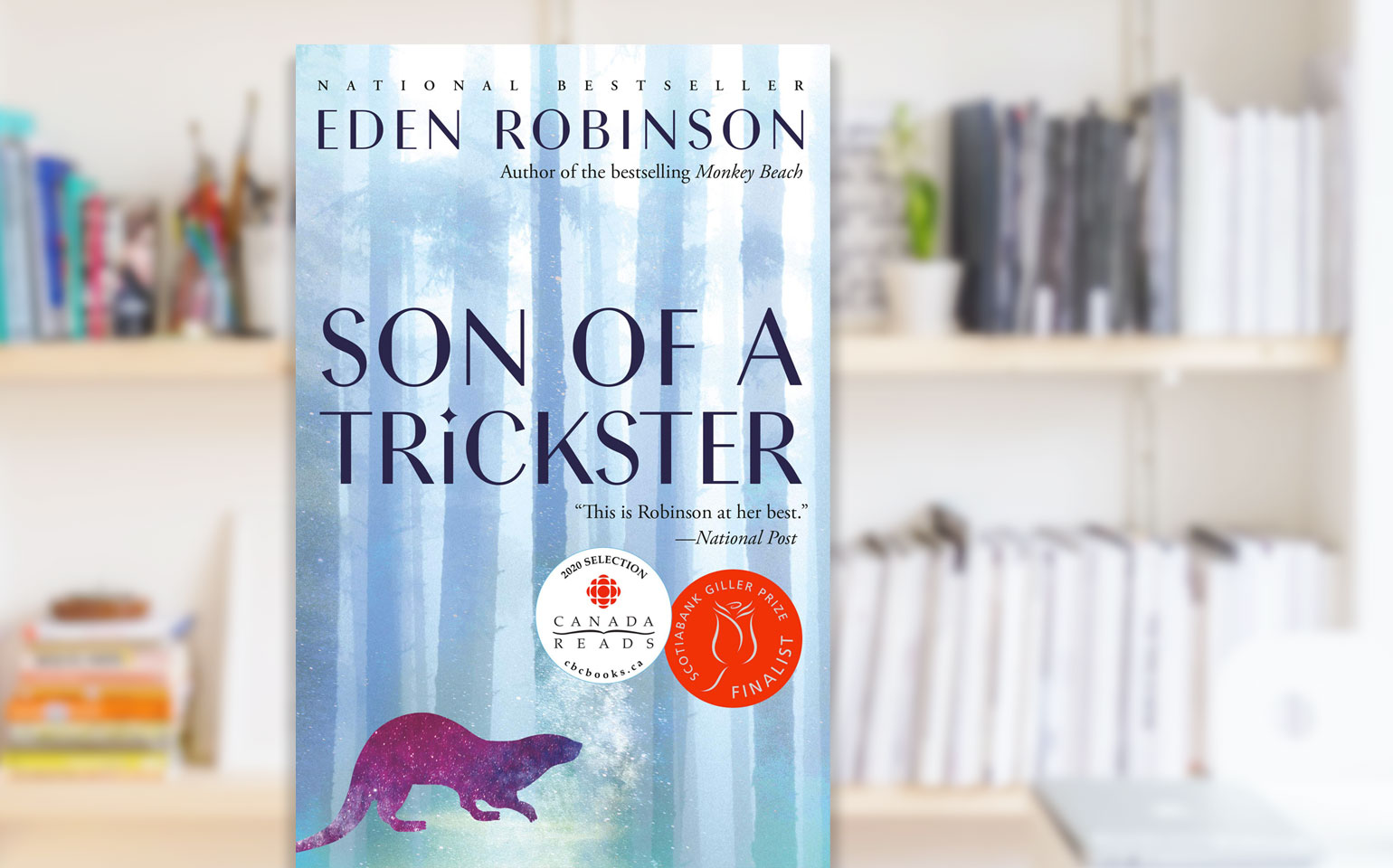

Eden Robinson’s Son of a Trickster: Down the Rabbit Hole

Eden Robinson’s Son of a Trickster (2017) is on my school’s English curriculum this year and we read it in my online book club. It is the first in a trilogy which plunges into a wild and wacky world of violence, family dysfunction, teenage angst and the supernatural. However, as the plot progresses, Robinson unveils a roller coaster of a coming-of-age novel. Much like her protagonist Jared, we the readers learn about a far more enigmatic world in which the normal and the magical, in the form of Indigenous lore, coexist.

On the very first page we realize that Jared is different. His maternal grandmother, Anita, dotes on her other grandchildren with treats and affection. Yet she gives Jared a jar of blood and animals’ teeth for his birthday and calls him the son of the raven “Weeg’it” or “Trickster”. We are now sufficiently intrigued, following the narrative as it charts Jared’s journey through a world of constantly shifting mysteries to a realization of who he really is.

After the first fantastical page, the story veers into Jared’s daily life characterized by alcohol and drug addiction, violence, sex and fickle relationships. Jared is sixteen and a stressed high schooler in a small town in British Columbia. He lives in the basement of his mother’s house and makes ends meet by selling weed cookies at school. His parents are not amicably divorced as he has to conceal from his mother that he visits and financially supports his father and his new family. His mother, prone to being drunk and stoned, often experiences violent fits of rage directed at him and others. Her relationships are chaotic at best.

It is to Robinson’s credit that she can depict cruelty and physical violence using colloquialism, pejorative diction and a matter-of-fact tone highlighting the self-perpetuating cycle of unemployment, financial hardships, addiction, abuse, and familial dysfunction within Indigenous communities.

At the beginning of the book, Richie, a petty drug dealer unleashes two manic pit bulls on Jared as revenge for debts unpaid by his mother’s now missing boyfriend. His mother rams the pit bull with her pickup truck and calmly drives over it while warning Richie to stay away from her son. The real kicker is that she tells Jared that Richie may come in handy, money and protection wise, so they shouldn’t burn bridges. Richie moves in with them shortly after. Even before Richie and her other missing boyfriend, there was David who seemed fine enough until he tried to break Jared’s ribs only to have Jared’s mom nail gun David’s legs and feet to the floor.

Understandably, to dull his senses and stay sane, Jared parties, drinks and smokes. It is too much for a sixteen-year-old to assume the responsibility of supporting and stabilizing his family in the absence of responsible adults save for his paternal grandmother, Nana Sophia. Even worse, Jared is deprived of the one source of unconditional love and affection at home from Richie’s remaining pit bull, Baby Killer, as Richie must eventually euthanize her. Yet Robinson injects this otherwise dreary tale with hope and optimism as Jared displays extraordinary compassion for others around him including his elderly neighbours, the Jakses, whom he looks after along with their messed-up granddaughter, Sarah who becomes his lover and girlfriend.

Adding to his stress on the earthly realm are the increasing interjections of the supernatural later in the novel. Even when he is sober, Jared frequently encounters a talking raven and an old, Indigenous woman who seems to have a creature living under her skin. After Jared gets stoned on magic mushrooms with Sarah, he begins seeing crawling ape-men everywhere. Next come visions of the dead Baby Killer and Sarah transforming into a river otter. Finally, Jared’s mother divulges that she, Sarah, and Mrs. Jaks, are witches and Nana Sophia, a high chief medicine woman. His mom performs spells to protect them from the river otters but Jared is knocked unconscious by someone. Then, Jared wakes up in a cave surrounded by river otters and his father, in raven form, rescues him by stopping time. His father also explains that he is Wee’git the “Trickster” and Jared is his son. Shortly after, Jared is cut off by Nana Sophia and the Indigenous woman with the monster under her skin, Jwa’sins, tells him she is Wee’git’s sister and takes Jared to an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. Jared begins to do better at school, gets a job at Dairy Queen, and hangs out with George, a stable friend. Most importantly he mends fences with his maternal grandma, Anita, who warns him to be cautious when dealing with these supernatural beings.

To some, this novel can seem messy and rambling as it takes the winding path to the fantastical which defines Jared’s identity. However, it is through navigating the “mess” that Robinson allows her readers to see Jared’s coming of age story; to truly grasp the difficulties teenagers like Jared face who, without adult guidance, must grow up quickly in order to simply survive in a cruel world. As his mother often tells him, “The world is hard. You have to be harder.” By the end, although Jared’s issues are not all solved, he is on a path to self-acceptance and redemption. Through Sarah he has a greater understanding of how connected he is to nature and the environment. He is also done with running away from his problems through alcohol and drugs, and is moving towards relationships uncomplicated by violence, abuse and mistrust.

Robinson’s Son of a Trickster defies a rigid novelistic approach which makes it a literary tour de force in Canadian Indigenous literature. As much as Jared ploughs through a series of difficult experiences to uncover who he is, so do we as we discover the complex world of Indigenous familial chaos, violence and escapism combined with its legacy of rich storytelling and lore that lie at its core.